The Cynefin Framework

Jun 26, 2025

The Cynefin Framework is a sense-making tool, a way of looking at reality, to guide our decision-making and action. It guides leaders in understanding the type of system or context they are in, and how to act accordingly.

Cynefin (pronounced kuh-nev-in) is a “Welsh word that signifies the multiple, intertwined factors in our environment and our experience that influence us (how we think, interpret and act) in ways we can never fully understand.” (The Cynefin Company)

Created by Dave Snowden at the end of the 90s when he worked for IBM Global Services, the purpose of this framework is to guide our decision-making and action by giving us a frame of reference that helps us make sense of the kind of system (or context) we find ourselves in.

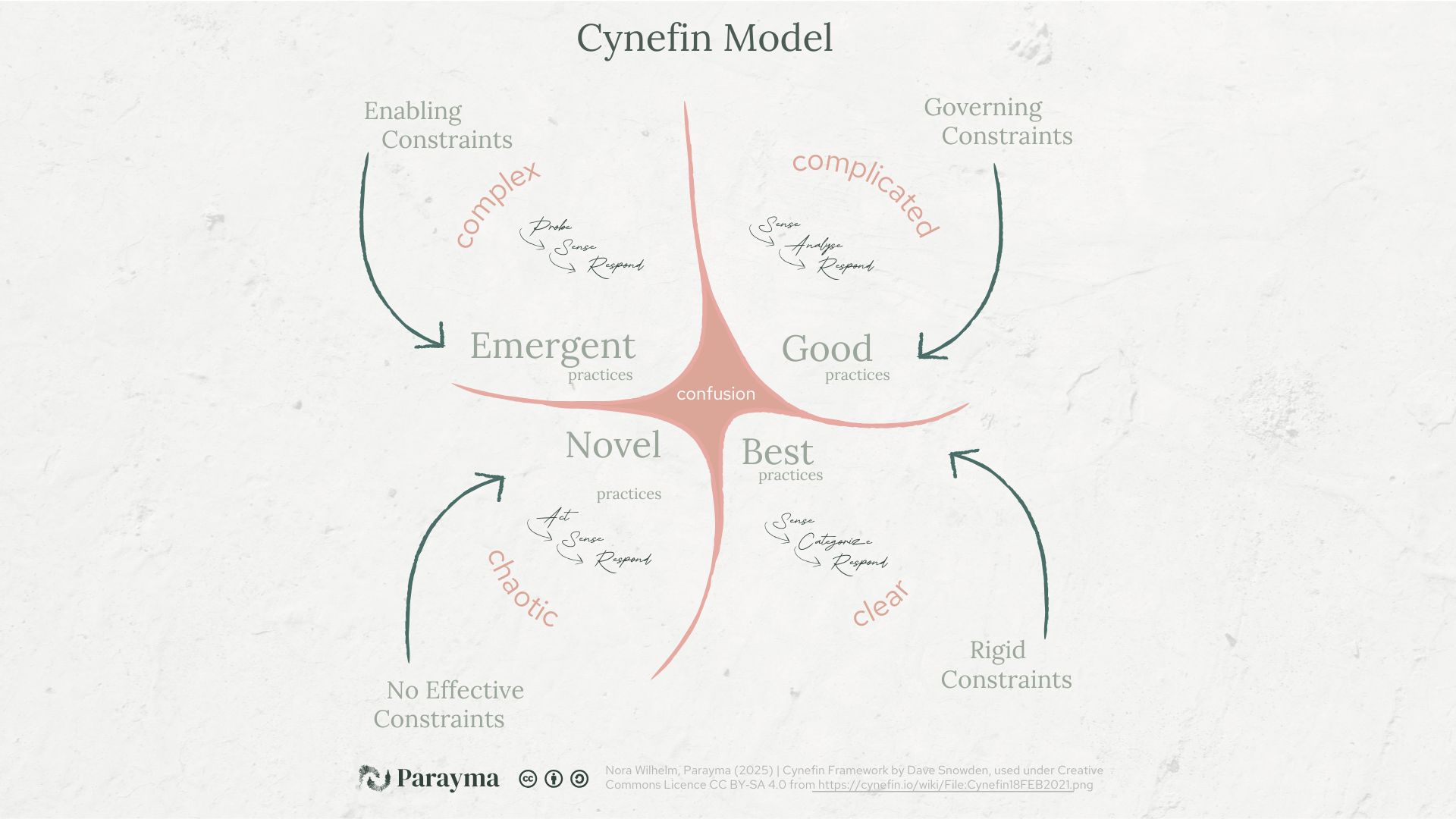

The Framework is composed of five ‘domains’ delimited by curved lines: Chaotic, Clear, Complicated, Complex and Confusion (also called Disorder in some versions of this model). We will explore each of them in turn below.

Confusion

Confusion is the state of not knowing what type of system or context you are in. When you first begin thinking in complexity or with frameworks, this is typically where people find themselves because we are not used to thinking in a multitude of different contexts. Indeed, most of us are trained to think and see the world in one specific way (e.g. in terms of laws, in terms of money flows, in terms of infrastructure…), and when all we have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. “We tend to assess a situation based on how we have already decided to act”, says Dave Snowden. It’s not a nice place to be in, as the system may be ordered but you are unable to see it, and therefore likely to get it ‘wrong’ in terms of trying to act strategically to get a certain result. The goal here is to get out of the ‘Confusion’ state through sense-making, and becoming able to assess what type of system or context we find ourselves in.

Clear

This is one of the two ordered types of systems, which means there is a linear relationship between cause and effect. In Dave Snowden’s words, “the same thing will happen again twice and not by accident, but by the nature of the system”. In the Clear systems, it is pretty easy for anyone to tell what the causal relationship is and nobody challenges that. For instance, we accept that we drive on a certain side of the road. This gives rise to a ‘standard procedure’, ‘best practice’ or ‘doctrine’ that everyone generally abides by. To understand what that best practice is, all you need to do is sense, categorise and then respond. For instance, sense which country you are in, categorise into the groups of countries that drive on the left VS those who drive on the right, and then respond accordingly by driving on the side that is the correct one in the specific country you are in. A well constructed Clear system does allow for exceptions, for instance swerving into the empty other lane because a child has run onto the street in front of you.

How to proceed:

Sense

Categorise

Respond

Best practice

(Rigid constraints)

Complicated

This is the second ordered system, where there is also a linear relationship between cause and effect, but seeing and understanding it is not accessible to everyone. It may depend on significant expertise, and require some type of analysis, such as investigation, research, testing… In order to be able to understand the causal relationship and, importantly, convince stakeholders and decision-makers of it. The course of action in a complicated system is to sense, then analyse before responding. Unlike the Clear systems where one best practice comes to dominate, in Complicated systems there may be various possible ways of doing things depending on the context, which means we can only achieve a certain level of ‘good practice’. An example here could be engineering a new type of technology, say a smartphone or a vehicle, where there is a customary approach (good practice) to include feature A and not feature B, but adding in feature B could be equally valuable and be considered ‘innovative’ by certain customers. Over time, as we innovate and develop the field further, good practice continues to evolve, and experts need to stay on top of the latest developments to remain relevant.

How to proceed:

Sense

Analyse

Respond

Good practice

(Governing Constraints)

Complex

Experts can be trusted within their field of expertise in complicated systems, e.g. a mechanical engineer or a mathematician can be trusted to know their stuff within their respective domains, but in a complex system it’s another matter entirely. Indeed, the best any expert can do in this context is to make a hypothesis based on their training, research, or prior experience - but that hypothesis may well be wrong. Which is not a problem in itself, but it is an issue when experts deem a system that is in fact complex as complicated and assume that they can figure things out or solve issues by relying only on their expertise.

This also leads us to lose trust in expertise, if the experts make a claim or try to get a situation under control and get it wrong. Indeed, a complex system is ‘multi-modular’, i.e. there is no clear relationship between cause and effect. I don’t know for certain what the right solution is until I act. This is the difference between building a piece of technology and, for example, the Brazilian rainforest, which is in constant flux and where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

In a complex setting, I probe by trying coherent (informed) actions or experiments that are safe, which then reveal what is possible, what works, etc, and allow you to respond further. Often, we see a pattern or understand how one thing eventually led to another in retrospect, and still our view usually remains partial as there are too many unknowns. In a complex system, anything you do changes the system, so it is essential to act thoughtfully and responsibly. We often “discover novelty through repurposing existing capability”, according to Dave Snowden. An ‘enabling constraint’ here describes a heuristic, a rule of thumb, some type of guideline. The way you can manage and make sense of a complex context is by trying to uncover the enabling constraints that already exist, that have historically emerged or naturally exist, and are guiding the actions of the participants in said system.

How to proceed:

Probe

Sense

Respond

Emergent practice

(Enabling constraints)

Chaotic

This is a type of system in which no order is possible. There are no constraints that can help us, everything is messy or all over the place. In their 2007 HBR article, Dave Snowden and Mary E. Boone write: “in a chaotic context, searching for right answers would be pointless: The relationships between cause and effect are impossible to determine because they shift constantly and no manageable patterns exist—only turbulence.”

The first action is to create a constraint. The first thing you do is act, then you sense, and then respond. Conversely, if you are in an ordered system, removing all constraints would effectively land you in a chaotic system. For instance, removing all rules around how we drive, or how we do bookkeeping, would result in chaos. Once we find ourselves in a chaotic context, stabilising action is what is required first.

This is the type of context where top-down leadership, ‘executive’ decisions and so on become justified, because asking for input or debating the right way to proceed is not something we would do in the living room if our house is on fire. The important part here is that we should not get stuck in this leadership pattern when the situation is no longer chaotic. Indeed, in a complicated setting for instance we should trust the experts (which includes people who are affected and know the challenge firsthand) rather than rely on top-down decision making.

How to proceed:

Act

Sense

Respond

Novel practice

(No constraints)

So applying the Cynefin Framework means using this knowledge to assess what kind of context we might be in (Clear, Complicated, Complex or Chaotic), and then act accordingly. Trying to act with the logic that works in one context in another is how we make a lot of mistakes and get it wrong. For example, people try to apply a linear approach in a complex context. Or a planning and controlling approach by foundations that seek to fund systems change, when in truth it is a field that only has enabling constraints and emergent practice, not good or best practice that always applies.

Understanding the distinction between these four types of contexts or systems helps us make important distinctions. We are not proposing that the type of approach that Complexity requires (probe, sense and respond to further develop emergent practice) should be used in contexts that are actually Clear or Complicated. What we are saying is that applying a Clear or Complicated approach to Complexity is unhelpful, and at worst, dangerous and harmful. I find this framework really helpful to communicate with stakeholders about what type of action or leadership is needed in each context, and to guide our own way of thinking and acting.

When we do systems change work, we necessarily find ourselves navigating complexity. It is imperative that we don’t fall into the trap of assuming our expertise will be enough to find ‘the answer’, or that indeed there is one right answer. Whilst we may be able to rely on existing information, research and the results of prior experiments, this is just enough to allow us to design a ‘coherent’ next step or intervention. We need to plan this carefully, as when we intervene we already change the system, and be prepared to observe what changes, and how. If we intervene and then end the project without harvesting or next steps, we have done the whole a great disservice. After intervening, we need to remain engaged, sense what is emerging, and respond again. As we are a whole movement working to address complex and social challenges, it is also essential to go through the planning process, as well as the sensing once the intervention has been implemented, in a collective way whenever possible. Include stakeholders and other organisations working on this issue, or at least do our best to share our insights. This also means communicating openly about our failures, because what we attempt should inform the next steps of other actors trying to support this system too.

How comfortable are you leading in all these different contexts? We all have natural preferences and tendencies, but if we want to be a true leader and changeworker, we need to develop the range to navigate all kinds of contexts, and train our response muscle to be able to react appropriately to whatever the system we are in calls for. It is essential for reliable collaboration, and also for us to be able to work towards paradigm shifts.

Sources & further reading

- The Cynefin Framework - A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making and Action, by the Cynefin Company

- The Cynefin Wiki

- Cynefin® - Weaving Sense-Making into the Fabric of our World, Book by Dave Snowden & Friends

- 2007 HBR Article by David J. Snowden and Mary E. Boone, A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making

Download the template

Applications now open

The Harvest Lab

8-week guided journey for changeworkers, thought leaders, educators, and visionaries ready to shape their lived experience into aligned offerings — and to do it in a way that feels regenerative, not depleting.

Subscribe to The Changework Journal

Get first access to new offers, free or discounted tickets to events Nora speaks at, exclusive access to funding opportunities we source from our network (not shared anywhere else on our channels), and more!